The Battle of Hastings 1066 & The Housecarl

(Plagiarized from various internet sources)

In the early morning of 14 October 1066, two great armies prepared to fight for the throne of England. On a hilltop 7 miles from Hastings were the forces of Harold, who had been crowned king nine months earlier. Facing them on the far side of the valley below were the troops of Duke William of Normandy, who believed he was the rightful king. By the end of the day, thousands lay dead on the battlefield, and the victorious William was one step nearer to seizing the throne.

By the evening of 13 October, the English and Norman armies were encamped within sight of each other at the place now known simply as Battle. Duke William of Normandy had had plenty of time to prepare his forces since landing at Pevensey over two weeks earlier. An invader in hostile territory, William’s intention was to force a decisive battle with Harold.

Harold, by contrast, had just won a hard-fought battle at Stamford Bridge, near York, where he had defeated another claimant to the English throne, Harald Hardrada, King of Norway, on 25 September. When the news of William’s landing reached Harold, he rushed the nucleus of his battle-weary army back south, stopping only briefly in London to gather any extra forces he could.

Soon after dawn on 14 October, Harold arranged his forces in a strong defensive position along the ridge now occupied by the buildings of Battle Abbey. The English line probably stretched for almost half a mile, and formed a ‘shield wall’ – literally a wall of shields held by soldiers standing close together – on the hilltop. This formation was considered almost impervious to cavalry, but left little room for manoeuvre.

William ranged his army to the south, at first on the far hillside above the marshy valley bottom. His Norman troops were in the center, probably with Bretons to the west and French to the east. These forces were in three ranks: the archers in front, then the infantry, and behind them the mounted knights.

There has been much debate about the size of the two armies. Some sources state that Harold had assembled a large army, but others say that he hadn’t yet gathered his full force. William’s army is said to have included not only Normans, but also men from Brittany, Aquitaine, France and Maine. The latest thinking is that both armies had between 5,000 and 7,000 men – large forces by the standards of the day.

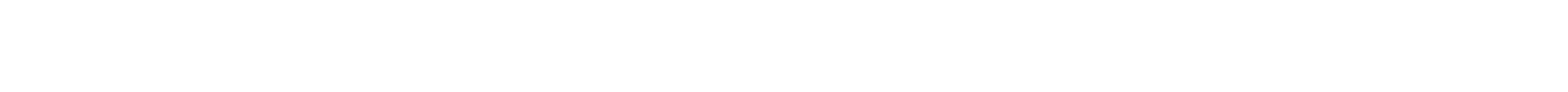

As the Bayeux Tapestry shows, both had horses, helmets, mail armour, shields, swords and bows. The Normans used their crossbows with great success on the dense ranks of the English. In contrast, English archers were in short supply – perhaps a result of the speed of Harold’s advance to Sussex, as bowmen probably travelled on foot.

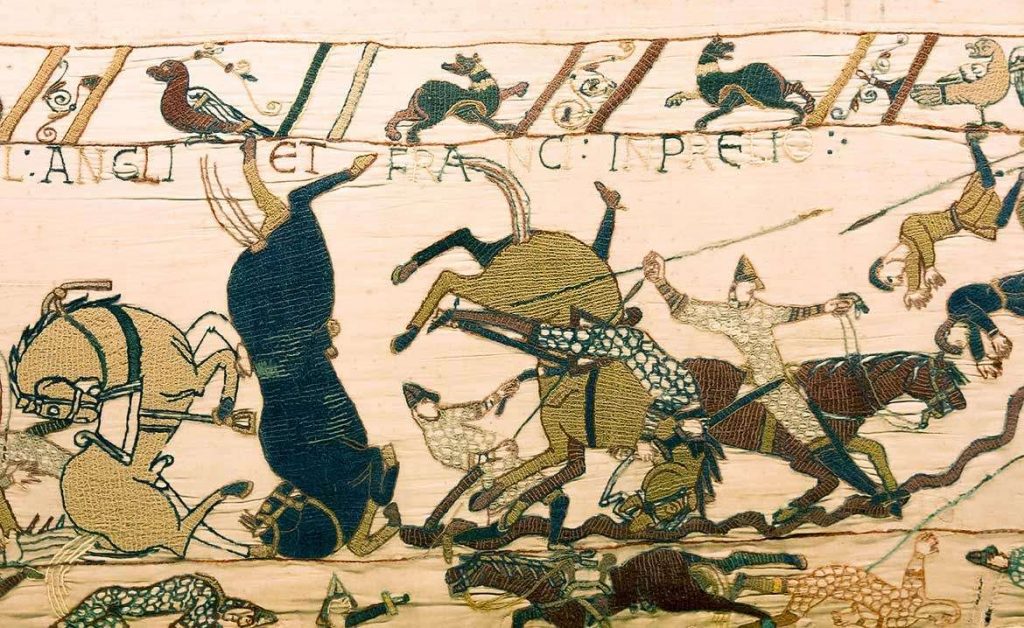

The main difference was the Norman use of cavalry. English armies used horses for getting around, but on the battlefield they fought on foot. The core of Harold’s army was his housecarls, perhaps the finest infantry in Europe, armed with their terrible two-handed battle-axes. In contrast, the backbone of William’s forces was his 2,000–3,000-strong cavalry force. At the Battle of Hastings, these different military cultures met head on.

At about 9am the battle opened to ‘the terrible sound of trumpets on both sides’. Then, as now, the landscape must have been open enough to allow the two armies to manoeuvre. The slopes were probably scrubby grazing land, with the ridge occupied by the English army backed by forests.

To win, the English needed to stay behind their shield wall, allow the Normans to be decimated in repeated assaults, and then sweep forward to defeat the invaders. In contrast, the Normans had to climb the slope to be within bowshot of the English – a couple of hundred metres at most – then fracture the English line with archers and infantry so the cavalry could ride through and finish off the broken remnants.

As William of Poitiers recorded, ‘It was a strange kind of battle, one side attacking with all mobility, the other withstanding, as though rooted to the soil.’

Harold’s forces repulsed the first Norman attacks, the English battle-axes cleaving the Norman shields and armour. William’s forces regrouped, but then some of them on the left flank, hearing a rumour that the duke had been killed, fled in panic. Some of the English began to pursue them down the hill.

To stop panic spreading and rally his troops, William rode out in front of them, raising his helmet to show his face and shouting: ‘Look at me! I live, and with God’s help I shall conquer!’ In a successful counter-charge, his troops surrounded the pursuing English forces on a hillock and annihilated them. The immediate crisis had passed.

For the rest of the day, the Normans repeated their assaults on the English shield wall. At least twice they pretended to flee in mid-battle, to encourage the English to break ranks and pursue them. They were partly successful, but the English line still held.

We can only imagine the grim scene: the hillside slippery with blood and littered with bodies, arrows, and discarded and broken weapons; the tiredness, hunger and fear of the surviving combatants; and the commanders shouting to rally their exhausted forces. William of Poitiers recorded that the Anglo-Saxons were so tightly packed together that ‘the dead could scarcely fall and the wounded could not remove themselves from the action’. William is said to have had three horses killed beneath him.

With the autumn daylight fading, the Normans made one final effort to take the ridge. By that time, Harold’s two brothers and other English commanders were almost certainly dead.

Then came the decisive moment: during the final assault, Harold himself was killed. There are differing accounts of how he died. One describes how an arrow struck him in the right eye, an event possibly depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry. But one of the earliest sources describes Harold being hacked to death at the hands of four Norman knights, in graphic detail:

The first, cleaving his breast through the shield with his point, drenched the earth with a gushing torrent of blood; the second smote off his head below the protection of the helmet and the third pierced the inwards of his belly with his lance; the fourth hewed off his thigh and bore away the severed limb.

By the early 12th century these two accounts had been conflated.

The Normans now began a last fierce assault. Leaderless, and lacking hope, the English forces finally gave way and fled. William of Poitiers described the scene:

the Normans, though strangers to the district, pursued them relentlessly, slashing their guilty backs and putting the last touches to the victory. Even the hooves of the horses inflicted punishment on the dead as they galloped over their bodies.

At a time when such contests were frequently decided within an hour, victory at Hastings was not certain until dusk, some nine hours after the fighting began – an indication of just how evenly matched and led the two armies were.

The Housecarls

Leading the battle on the English side, Harold’s housecarls stood proud atop Senlac Hill, their shields locked in the warrior wall erected to prevent William’s march into England. As the Norman knights charged up the hill, occasionally a brave man would step out of line, wedge his shield into the earth and swing his great two-handed Dane axe. Such was its momentum that it might cut horse and mail-clad rider in two.

These soldiers had already defeated the army of Harald Hardrada of Norway, the most feared Viking king of the time. Although they’d not even had three weeks to recover from the Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September, the confidence born of that victory must have sustained Harold and his men on the march south and as they formed their shieldwall. The housecarls were the elite troops of their age. Now, tested again, they would prove it.

Only, as we now know, they failed this final test. Many had fallen at Stamford Bridge, but even with their numbers depleted, they withstood William’s men for a long, bloody day at Hastings – when most early-Medieval battles ended within an hour. Even when King Harold fell, most of his housecarls fought to the death.

To explain the valour and combat strength of these troops, scholars examined the records of the time to find what set them apart from the norm. The majority of Harold’s army was composed of the fyrd, the muster of free men called upon to take up arms in service of their king. These were farmers and artisans, armed with spears, wearing leather jerkins and carrying shields. They were strong and brave men – you couldn’t take your place in a shieldwall without bravery – but not elite soldiers. The housecarls were different.

The great two-handed Dane axes were their characteristic weapon and something that set them apart from the thegns of the pre-Cnut era. But, in most other ways, they were indistinguishable from the thegns who had long served the Anglo-Saxon kings.

Thegns had started out as warriors, members of the warbands that the first generations of Anglo-Saxon kings gathered around them, held to service by the gift-giving of the king. As time passed, the duties of the thegn broadened. As reward for service, a thegn would be gifted land, where he acted as the king’s representative, but this land returned to the king upon the thegn’s death. However, with the rise of monasteries, this reversion of land became untenable: institutions needed to own their land in perpetuity so that they could adequately plan for the future. So, from Offa onwards, the Anglo-Saxon kings developed the idea of bookland, where ownership of land was inscribed in deeds into books of record.

We can say that recent scholarship indicates that the old idea of housecarls as a discrete body of men, bound by their own law code and acting as the king’s standing army is false. After Cnut’s conquest, the terms housecarl and thegn seem to have been used interchangeably, with the only significant difference being that housecarls were originally more likely to be Danish. As high-status warriors, they were still called upon to serve king and lord and, by virtue of their training and weapons, they did form an elite group of infantry. As the men of Harold’s household stood on Senlac Ridge, fingering the shafts of their Dane axes, they must have been confident in their ability to see off this new pretender to the crown of England.

We know they failed, but of those that survived, many went into exile and, taking their martial skills with them, migrated east to the court of the last Romans, the Emperors of Byzantium. In the aftermath of Hastings, English housecarls went on to form the backbone of the emperor’s Varangian Guard, which became known as an Anglo-Saxon force. From the ends of the earth, the last housecarls finished their service at the center of the world, serving the last emperors – a fitting swan song.